Opera reimagines Sacajawea's story from her Indigneous perspective

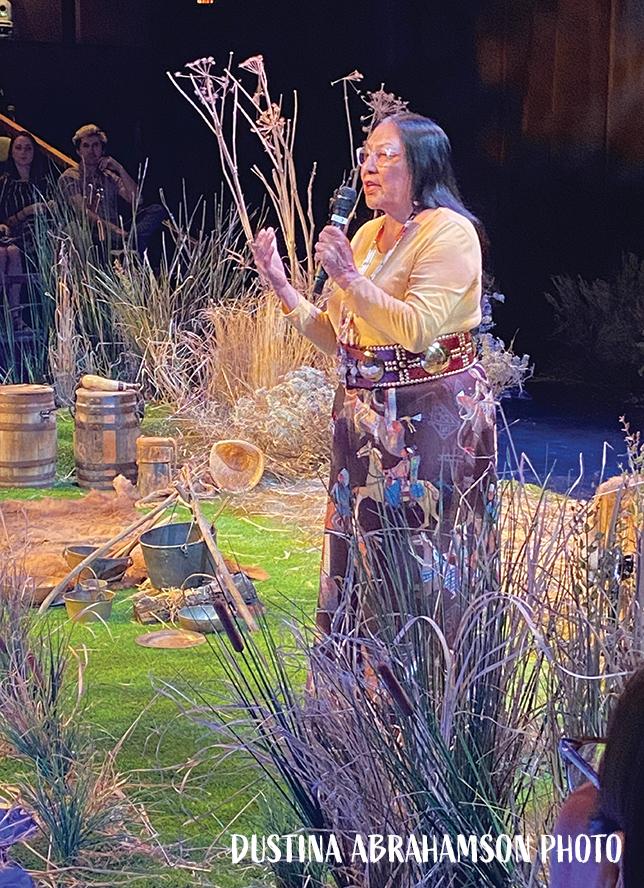

Rose Ann Abrahamson joins the cast of the "Nu Nah-Hup" opera on stage in Portland, Ore.

By JASON VONDERSMITH

Pamplin Media Group

PORTLAND — As a living relative, Rose Ann Abrahamson never wants people to forget about the Native American interpreter and guide Sacajawea’s contribution to the Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804-06) into the United States’ west.

But, Sacajawea’s story needs to be told from her Indigenous perspective, and not just the white man’s perspective, said Abrahamson, a culture bearer with the Agai-Dika/Lemhi-Shoshone in Idaho — Sacajawea’s tribe. All across the country Abrahamson has shared the same message: Sacajawea’s legend has a story to tell, and it’s not the same narrative we’ve all been taught.

The librettist and creative lead Abrahamson, in collaboration with Opera Theater Oregon Artistic Director Justin Ralls and Native American composer/flutist Hovia Edwards, helped create the opera “Nu Nah-Hup: Sacajawea’s Story,” and 35 minutes of the developing work was on stage 7:30 p.m. Saturday, May 13, and 2 p.m. Sunday, May 14, at Hampton Opera Center, 211 S.E. Caruthers St.

The reimagined opera of familial cultural history, which will be made into a full-length production eventually, was inspired by one entry from the Lewis and Clark Expedition journal of Aug. 14, 1805, in which William Clark described an incident where Sacajawea was physically struck by her husband, the French-Canadian Toussaint Charbonneau. Her husband was an abusive man, and Sacajawea was a saintly woman and certainly an important person in the history of the United States, Abrahamson said, yet many people have not been educated on real history.

“It tells the story of a young woman who had undaunted courage,” said Abrahamson, who’s the great-great-great-grandniece of Sacajawea. She first started learning about Sacajawea through oral history at age 6. She’s now 68.

“She showed the strength of women — our mothers, grandmothers, ancestors, about women around the world who show ability, tenacity and strength. She represents that.”

Rose Ann Abrahamson speaks at the opera production.

She added: “We’re doing something no one has ever done. It’ll be very unique. … What I observe and what I have felt is that this opera can bring you to tears, you feel the emotion and beauty of what is told and presented.”

Authentically portrayed

The opera features authentically replicated regalia — including Sacajawea’s blue beaded belt, which was given to the U.S. president back then, made by Abrahamson’s daughter — and native Agai-Dika (“Salmon Eaters”) language, as well as Quebecois French, English and Native American Sign Language, as organizers want to firmly document and preserve the Agai-Dika dialect and language. Music, soundscapes and a chamber orchestra add to the environment. The flute being special in Native American culture, it helps set the emotional tone of the story.

Canadian soprano Marion Newman plays the role of Sacajawea, while Richard Zeller portrays Charbonneau and Dan Gibbs is Captain William Clark.

The domestic abuse scene, while known, perhaps had been overlooked as significant, Abrahamson said. She has spoken about Sacajawea’s story throughout the country and often fields the question, “Why didn’t she stay with her people, or run away?” This story, she added, will answer the question in a beautiful way.

“I like to do research, I do a lot of history, and I wanted to present this history of this brave young woman and what she had been through,” Abrahamson said. “The title we chose, ‘Nu Nah-Hup,’ it’s a very powerful statement: ‘What happened to me.’”

Sacajawea felt compelled to help the expedition, which she did by showing Native American tribes that Lewis and Clark came in peace. It’s no wonder that she eventually relented and traded her blue beaded belt to the white man, and it was sent to the President Thomas Jefferson.

“She was 16 (and with a baby). They treated her well,” Abrahamson said, of Lewis and Clark. Further appreciation was given to Sacajawea when she saved the journey’s documents during a rafting trip. They started paying Sacajawea respect by referring to her simply as a Native woman (rather than a derogatory term). “They started seeing her as a human being and of value, and she became an even greater value when they reached her people (Shoshone, as well as Nez Perce),” Abrahamson said.

“All the way through she played an important role.”

Abrahamson has shared Sacajawea’s story with many groups. And, she helped push through the construction of the Sacajawea Interpretive, Cultural and Educational Center in Salmon, Idaho, in Lemhi County. Unfortunately, Abrahamson once lived in Salmon with her aunt and uncle but a property dispute led her to move to the Shoshone-Bannock/Fort Hall Reservation in southeastern Idaho.

Shoshone-Bannock flutist Hovie Edwards performs.

Opera collaboration

Opera Theater Oregon, of Portland, is dedicated to social justice, political and environmental issues.

Abrahamson brought Ralls to Salmon to witness the environment and visit the village site.

Ralls has done other social justice projects, but said “I don’t believe anything like this has been done with all different components particularly with creative leadership of Rose Ann.” It’s Indigenous-forward and Indigenous-focused, and not developed through another, non-Indigenous person’s storytelling.

In the scene in question, Meriwether Lewis had gone ahead of the group to connect with Sacajawea’s people to trade for horses. Clark took note of the striking incident, and it was important enough to write about.

“We’re taking one line in a journal and expanding it through the Indigenous perspective of Sacajawea,” Ralls said. “Rose Ann and the team have led an effort for historic authenticity at every level. It began with language — it’s Rose Ann’s perspective that Sacajawea speaks Quebecois French, English and Shoshone — to Shoshone regalia.”

Ralls and Edwards have worked on music. Edwards composed a prayer and lullaby, “Nu-zhee-zhee,” which means “My Child,” which Sacajawea recites to her daughter. Ralls arranged and orchestrated melodies.

“We’re scoring Rose Ann’s vision,” he said.

Ralls said he, Edwards and Abrahamson will keep working toward making “Nu Nah-Hup: Sacajawea’s Story” a full production, which would entail finding investing partners. It’s the recipient of the 2022 Native Voices Endowment Award from the Endangered Language Fund at Yale University, and it’s supported by funding from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Oregon Community Foundation’s Creative Heights Grant.

Katherine Goforth is the stage director and dramaturg.

Abrahamson is joyous that the opera helps preserve Agai-Dika language and culture. A woman once told her that Shoshone cannot let white man take their land, but most importantly “don’t let them forget us.” Abrahamson has dedicated her life to not allowing that to happen.

Rose Ann Abrahamson with her family at the production.

“What’s really urgent is our language is slowly dying,” she said. “The speakers right now are 60 and over in our dialect and there are very few of us. Just like certain English dialects. Other Shoshone tribal groups are losing their language, too. It not only preserves through music language heard by the (current) seventh generation, we believe that we have to struggle and fight. You can imagine the incredible effort of colonization and assimilation that we’ve endured. Today we’re still here, but we want to preserve the beauty of the creator’s gift.

“Now we want to take this history and this knowledge to a different level. This is another way to preserve.”

Rose Ann said she and Hovia enjoyed working on the project that told about what happened on August 14, 1805 (documented in the Lewis and Clark journals) with history, story and music from a Native American perspective.